TraOnna, a Brutus in Vans tennis shoes, believes Cassius is behaving with considerable dishonor.

Under stage lights Downtown, TraOnna scolds Daynell for corrupting the assassination of Julius Caesar by tolerating bribery.

“Brutus, bay not me,” Daynell snaps back.

The eighth graders work through initial nerves to show themselves as the caliber of students who can elevate a convoluted Shakespearean text into a plausible argument between teenagers.

Back at school, Daynell Griffin and TraOnna Malloy, both 14, share the frustration that they feel they have to work harder than white students to prove their intelligence, simply because they’re black girls. They’re both engaged, curious students, taking on Shakespeare and August Wilson in the mornings, and leaning on the other’s strengths if a homework problem won’t unravel or a thesis statement doesn’t read right.

But the school district treats each girl very differently.

Daynell Griffin (left) and TraOnna Malloy, both 14, act out an argument between Cassius and Brutus in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar at the Pittsburgh Public Theater. (Photo by Guy Wathen/PublicSource)

TraOnna is, officially, “gifted.” A designation that opens access to specialized, outside-the-box education, as well as approval for higher-level courses when she goes to high school next year.

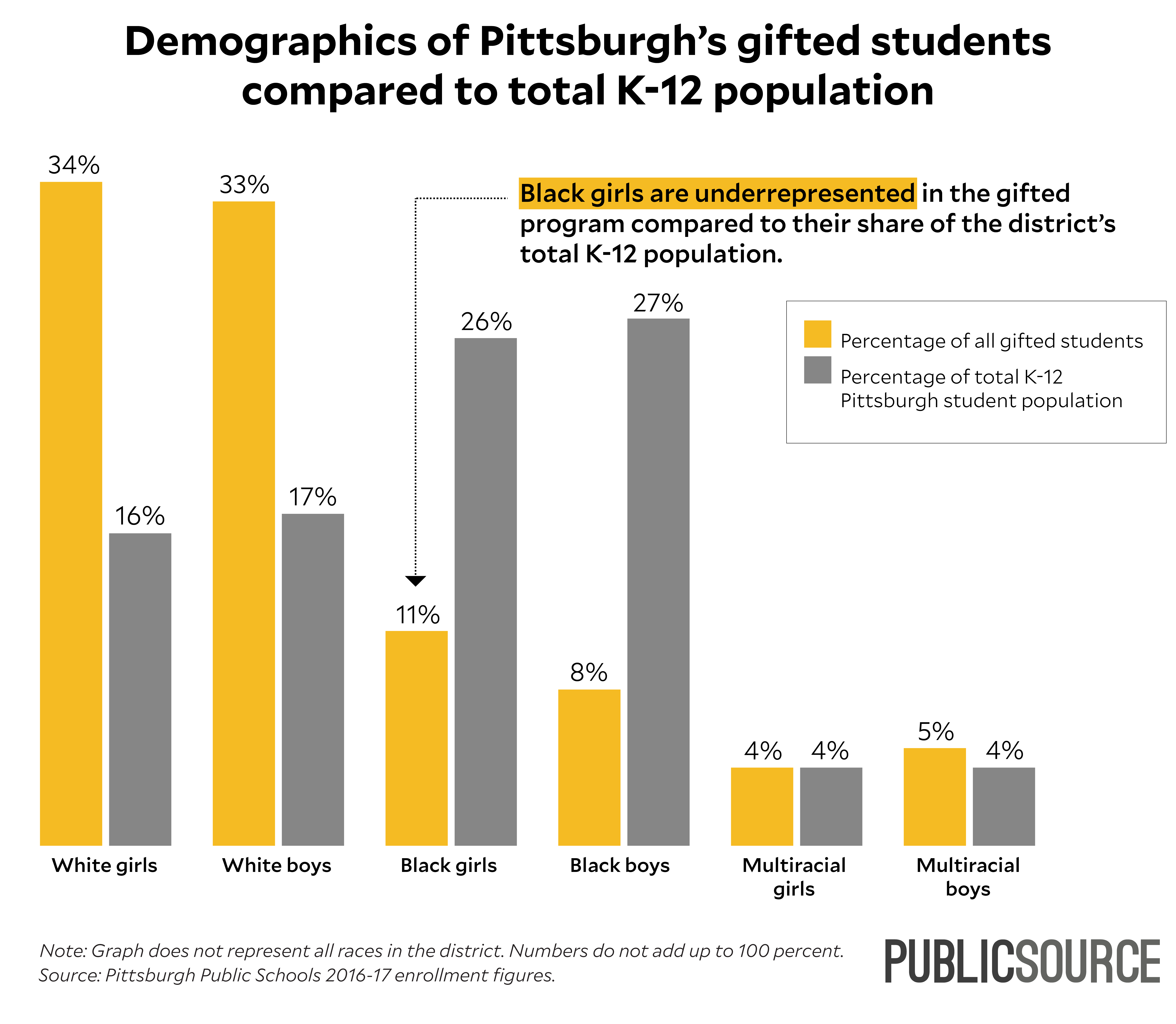

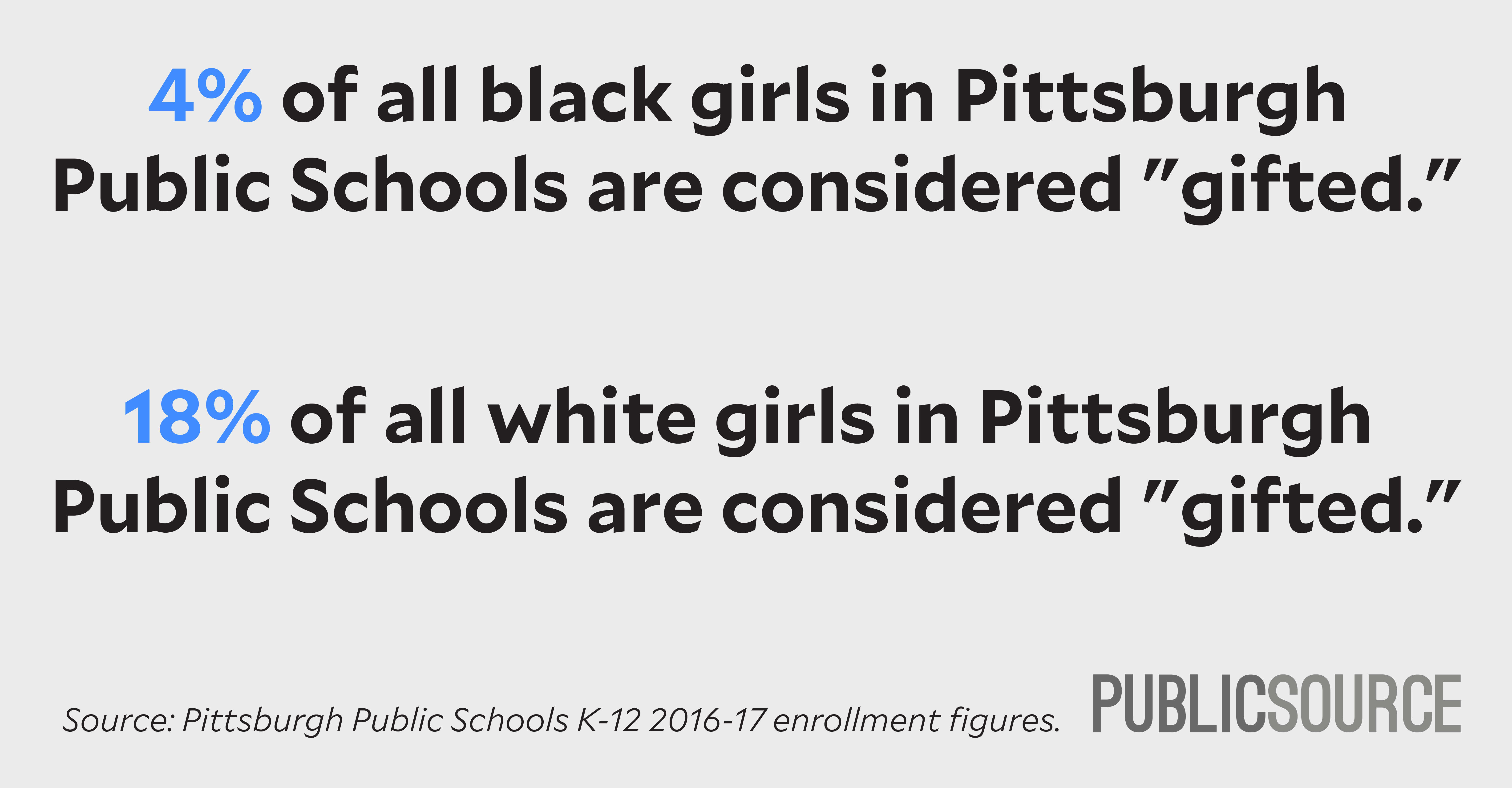

Four percent of black girls in Pittsburgh Public Schools get that treatment.

It’s different for white girls; 18 percent of them get picked, with access largely hinging on whether teachers realize a student is exceptional, or if parents know to push for testing.

So once a week, TraOnna boards a bus, riding with a bunch of white kids from Colfax K-8 in Squirrel Hill to the district’s gifted center, while Daynell, and many others, don’t get to go.

The lack of equality isn’t lost on them. They get the impression that one black middle schooler from every grade at Colfax gets picked to ride the bus, including TraOnna and Daynell’s younger sister Donise – though white kids who go don’t seem any smarter.

“We see it, but it’s like they don’t see it,” Daynell says of administrators and teachers, explaining the inequality and what seems like an indifferent system.

But the district is well aware. Officials at Pittsburgh Public Schools acknowledge the disparity, see it as unacceptable, and say they’re trying to rectify yet another inequality heaped on students of color.

“It’s been changing,” said Kashif Henderson, coordinator of K-12 gifted and talented, explaining that he’s seeing more diversity at the Pittsburgh Gifted Center at Greenway.

But rather than lauding the achievement, he couches it as “not a significant increase.”

Who gets to be ‘gifted?’

Which students, and with which skin tone, are granted opportunities in the classroom is one of the oldest and thorniest questions in public education. A straightforward problem — why don’t we have equity? — is met with the frustrating answer that our schools still haven’t learned to be fair.

White students get better opportunities more often, and seemingly with fewer barriers than students of color.

“Let’s face it: White students definitely are overrepresented in the gifted program,” said Lynda Wrenn, a school board member who previously served on a task force focused on access equity in gifted education.

In all, white students make up two thirds of the district’s gifted students, according to enrollment data. Only one third of Pittsburgh’s K-12 population is white.

The disparity is easy to recognize, but officials have considerable work ahead if something’s to be done about it.

“As a district, we know that, we admit that, we don’t shy away from it,” Henderson said of the scope of the job. “We don’t deny it. I think we embrace it.”

Being “gifted” gives a student clear benefits compared to those who don’t get the label.

Through eighth grade, students are bussed once a week to a specialized center where they attend higher-level classes designed to suit their academic strengths and interests, along with an individualized education plan based on those same strengths. In high school, students are qualified for advanced college prep courses, based on a designation they may have earned in kindergarten.

In his second year as gifted and talented coordinator, Henderson is overhauling the district’s identification process and working with a faculty team focused on equity to reduce the likelihood of qualified students being left out. That involves things like expanding how students are evaluated and training teachers to avoid biased selection.

“My goal is to discuss opportunity,” Henderson said. “How do we make sure that our principals and teachers understand giftedness?”

TraOnna Malloy, 14, feels singled out as a black girl at the Pittsburgh Gifted Center, where most of her classmates are white. (Photo by Guy Wathen/PublicSource)

‘People that know’

But how did we get to that troubling 4 percent number in the first place?

The problem is rooted in a combination of imperfect IQ testing, reliance on teachers to equally recommend potentially “gifted” students, and a system that benefits students whose parents push to get them included.

National statistics show that a black student with achievement scores equal to a white student is far less likely to get gifted education.

In Pittsburgh, Wrenn described a process where parents learned about gifted testing through word-of-mouth at the bus stop.

Pamela Harbin, co-founder of the Education Rights Network, thinks a process based on staff referrals and parental pressure creates an exclusivity.

“That’s how the system works,” Harbin explains. “The people that know about it tell the other people they know.”

She bluntly calls the result “segregation,” where one set of opportunities is available mainly to white students, and students of color are selected far less often.

So you get an awkward scene like TraOnna sitting in a class at the Greenway gifted center called “Black Minds Matter,” wondering why her black friends from Colfax aren’t there.

“That makes me feel so left out,” she says, explaining how isolated she feels in gifted classrooms far whiter than the district’s student population.

Daynell said she was considered gifted in the Wilkinsburg School District, but lost the designation when she moved to Colfax last school year.

Being left out made her feel bad, Daynell says, because she feels she should belong.

Daynell Griffin, 14, believes she’s smart enough to be considered “gifted” but was not selected to attend the Pittsburgh Gifted Center. (Photo by Guy Wathen/PublicSource)

Eventually, she decided she didn’t care anymore because she doesn’t view the students who participate as inherently smarter.

“There’s a lot of smart ones who should be at Greenway but didn’t make it,” Daynell says. “It’s just not fair.”

Teacher bias, advocacy

Kipp Dawson plainly sees the exclusion.

“I have, every year, some personal experience with some kids who are not seen as qualified for classes to which they would make a huge contribution,” says Dawson, who teaches middle school English at Colfax.

She beams at the portrayal of Brutus and Cassius by TraOnna and Daynell — roles that for centuries went to white men. It’s in her morning class where the girls rehearsed their scene from Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar before performing it last month on the home stage of the Pittsburgh Public Theater.

It’s clear she sees them as engaged and talented students, regardless of any official designation.

“By doing the work that you’re doing,” she tells the girls after school, “you are helping to shake things up.”

But teachers, especially in lower grades, can also be a problem.

Because not all students are tested, teachers become the gatekeepers, charged with picking out students they feel are above and beyond their classmates.

Kipp Dawson (right), an English teacher at Colfax K-8, tells Donise Griffin (left) and Shakyna Golphin (middle) about her efforts to bring racial diversity to the school curriculum. (Photo by Guy Wathen/PublicSource)

A vast nationally representative dataset shows how things go wrong.

Jason Grissom, a researcher at Vanderbilt University, analyzed federal data that tracked a representative cohort of students through eighth grade. After filtering both the race of students and the race of teachers, he realized that when teachers are white, black students seemed to be assigned to gifted services at lower rates.

That disparity disappears when teachers are black.

In those cases, black students are referred almost equally to white students, according to the study he co-authored.

This could be cultural bias, Grissom said. Experts describe common scenarios such as white teachers seeing white students as outspoken but when students of color behave similarly, they see it as disrespectful. Teachers may also disregard slang they don’t know or miss nonverbal signs of a student’s giftedness.

The finding needs further examination, Grissom said, and could also be influenced by black students performing differently in classes with a teacher who matches their culture. Or it could be influenced by parents advocating more assertively for their student if the teacher shares their culture.

Shakespeare from the Hill

For Daynell and TraOnna, not having their culture respected is a recurring gripe.

WIth Shakespeare wrapped, Dawson’s course at Colfax shifts the focus to playwright August Wilson, an intentional move to expose the middle schoolers to diverse work representative of the student population.

The girls are enamored with his work. A black writer from Pittsburgh who reached such acclaim while capturing the poetry and nuance of life in the Hill District.

Daynell thinks he’s a “fabulous writer.”

“Shakespeare in a black mind,” TraOnna calls him.

TraOnna sees her personality in Troy from Fences. Not the bullying and infidelity, but how he holds his feelings in until they get to the point of bursting. Daynell is drawn to Troy’s wife Rose, who forms the play’s emotional core.

But some white students seem less enthralled, the girls say.

Students who have no problem with the wonky “thees” and “thous” of Shakespeare but think it’s strange to have a writer using the slang of black residents from their very own city.

TraOnna feels that same tension at the gifted center.

Yes, she has friends there, but she feels she sticks out simply for being a young black woman.

Because so few students look like her, she says she feels like some peers try to test her, to see if she’s intelligent enough to really belong.

Or they condescend, acting like she’s so much smarter than her friends who stay at Colfax. She’s sure that’s not true. But without systemic changes, the district’s selection of gifted students is doing little to dispel that feeling, even if students left out aren’t actually less intelligent.

“I might be in the gifted program, but I still need help,” TraOnna says. “You can’t just base it on, ‘Oh, you go to gifted? Oh, you’re smarter. Oh, you’re white? You’re smarter.’”

PublicSource Interactives and Design Editor Natasha Khan produced the graphic and quiz for this story. The quiz was built from open source code created by developers at Mother Jones.

Reach Jeffrey Benzing at jeff@publicsource.org. Follow him on Twitter @jabenzing.

Quiz: How gifted are you?

Disclaimer: This quiz is just for fun, based on questions created by TestingMom.com to prepare students for “gifted” screening. The answer choices with A, B, C, D may appear out of order, so just be aware of that while taking the quiz! Your total test score will be tallied at the bottom of this quiz.